To See Colour Or Not To See colour?, That Is The Question!

Normally, human eyes have three different cones (S-cones, M-cones, and L-cones) which are each sensitive to different visible wavelengths. By comparing the amount of light signalled by different pigments, humans can distinguish around a million different colours. Sharks on the other hand are cone monochromats, meaning they only have one functioning type of cone in their eyes which allows them to easily distinguish patterns but not hues.

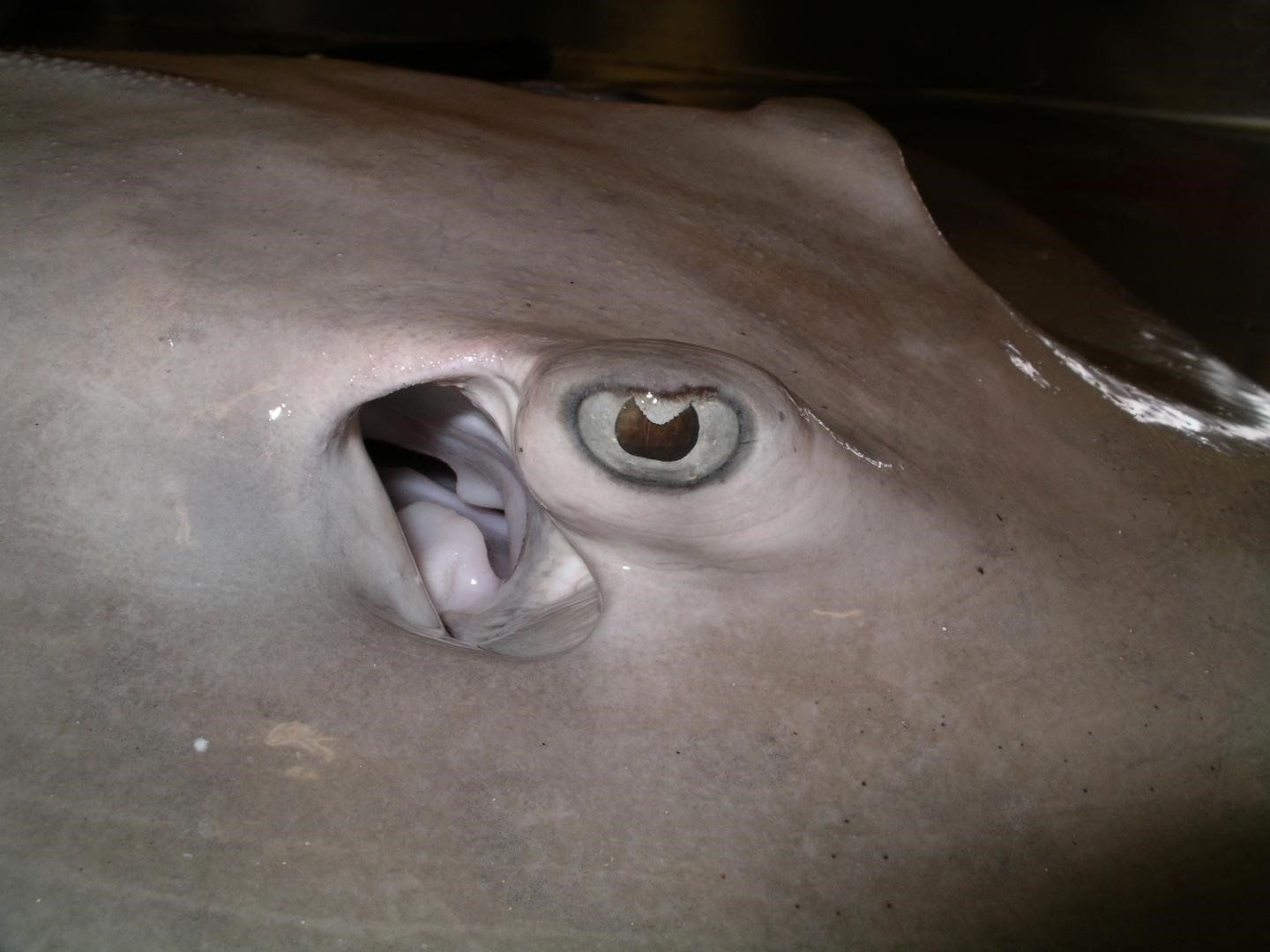

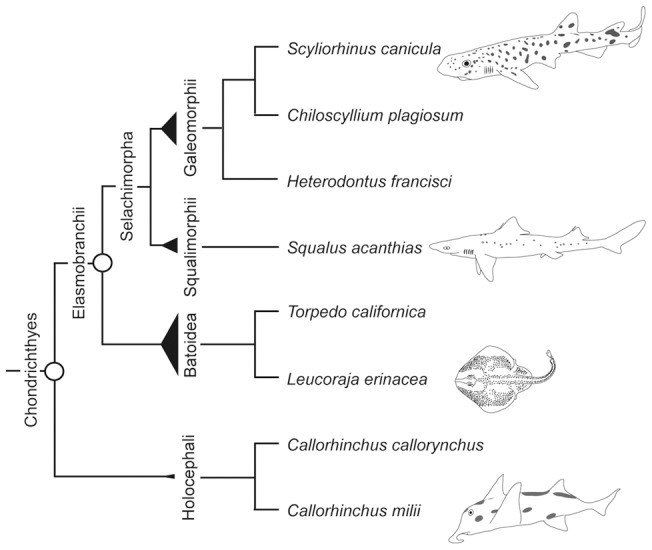

Opsin, a group of light-sensitive proteins, are found in the photoreceptor cells of the retina. All cartilaginous fish have lost the SWS1 and SWS2 opsin genes. However, rays possess two cone opsin genes whereas sharks have evolved to only possess one. As a result, it appears that rays are cone dichromats with minimal colour vision, while sharks are completely colour blind.

Why would seeing colour matter to some species?

Colour discrimination can be useful to animals when detecting prey, avoiding other predators, and choosing mates. Rays, for example, feed predominantly on benthic crustaceans and molluscs; therefore, they spend much time resting on or buried under the sandy sea floor. As a result, some colour vision may enhance visual contrast and help them detect overhead predators. Sharks, however, seem to have a unique opsin adaptation, likely due to the range of light conditions during hunting, that renders them colour blind.

How could being colour blind benefit other species?

Since ocean water and any dissolved or suspended particles tend to absorb, reflect, and scatter light, visual contrast is quite low in the primarily blue-green aquatic environment. Additionally, sharks are active both day and night, meaning they operate under a wide range of light intensities, and thus differentiating colour is not nearly as important as differentiating light contrast.

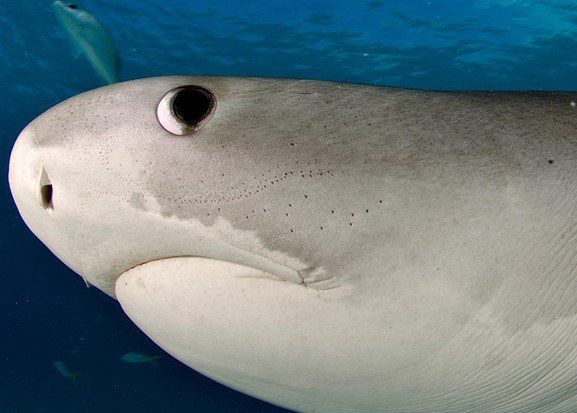

Like humans, sharks have cones and rods in their retinas, both of which are stimulated by light. Rods detect low light vision, whereas cones are optimal for bright light vision. However, only cones are associated with colour; rods are more relevant to measuring brightness. In sharks, rod cells are the most common type of photoreceptor, meaning they can see within a wide range of light levels. The contrast sensitivity of the shark eye is therefore likely a visual adaptation to conditions with low visual contrast or low light intensity. Additionally, to aid in variations of light intensity throughout the day and when moving between shallow and deep water, some shark species have mobile pupils that constrict in bright light to form a slit.

Furthermore, sharks have unique electro-field sensors, allowing them to detect prey by sensing the weak electrical fields generated by muscle movement. With this strong “sixth sense”, sharks are much less reliant on their vision, and have no need to see in colour.

Similarly to sharks, other large marine predators, such as dolphins, whales, and seals, are also colour blind. Since most of these animals do not have various body colour patterns, it again makes sense that colour vision is of little use for intraspecific communication.

But why did sharks lose the cone opsins that were present in their gnathostome ancestors in the first place?

While we cannot be completely certain, many scientists have agreed on one hypothesis. About 359 million years ago, sharks and other cartilaginous fishes (Chondrichthyes) diverged from their ancestral species. During this time, the rise of large predatory marine animals could have driven many fishes to seek safety and find new food in the deeper parts of the ocean. As a result, there could have been a strong selection for visual adaptations that enhanced vision in conditions with less light. Such adaptations may have led to the loss of opsins or cone types, which were no longer necessary and only took up valuable retinal space.

Overall, the relative simplicity of shark retinas makes sharks a useful counterpoint for the study of vision in other animals. The loss of all but one cone type, and even the possible loss of all cones in a few shark species, provides a unique opportunity to study the physiology and anatomy of monochromatic visual systems and allows scientists to learn more about these incredible species.

References:

Hart, N. (2020) ‘Shark and ray vision comes into focus’, Molecular Biology and Evolution .

Hart, N. (2020) 'Vision in sharks and rays: Opsin diversity and colour vision', Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2020.03.012

Karul, Ç & Nazlioglu, S. (2015) ‘The flexible Fourier form and panel stationary test with gradual shifts’ ResearchGate . Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Sharks-skin-inspires-scientists-to-design-a-b-hygienic-floor-wal... (Accessed 12 June 2020)

King, B., Hu, Y., Long, J. (2018) ‘Electroreception in early vertebrates: survey, evidence and new information’, Palaeontology , 61(3), pp. 325–358.

Skerry, B.J. (2011) 'Sharks Are Colour-Blind, Retina Study Suggests', National Geographic. Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2011/1/110119-sharks-color-blind-eyes-rods-cones-australia-a... (Accessed: 10 June 2020).

Renz, A.J, Meyer, A., Kuraku, S. (2013) ‘Revealing Less Derived Nature of Cartilaginous Fish Genomes with Their Evolutionary Time Scale Inferred with Nuclear Genes’, ResearchGate . Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Species-tree-illustrating-the-relationship-of-all-chondrichthyan... (Accessed 12 June 2020)

SHARE THIS ARTICLE