See Turtles: the Importance of Insights provided by sea turtle citizen science in the UK and Ireland.

Sea-turtles: The Importance of sea-turtle citizen science in the U.K. and Ireland.

Joshua Hayes | February 4th, 2021.

Whether it is the result of citizen science (i.e.RSPB Big Garden Birdwatch) or via surveys and studies conducted by trained professionals, recorded sightings of any animal can prove valuable to our scientific understanding of the species in question.

Providing insights into the presence-absence, range extensions, habitat usage, habitat fragmentation, and population levels of marine animals, can be used to improve our understanding of the ecological impacts they face as well as monitoring ongoing conservation efforts.

Sea turtles are probably one of the last species most people expect to see swimming within our stereotypically cold coastal waters or lounging about on our sometimes-frigid beaches. And you would be forgiven for scoffing at the thought, after all most species and populations are considered to be endangered, and associated with sun, sand and far away lands. However, between the United Kingdom and Ireland, the general public, governmental organisations and programmes such as the Scottish Marine AnimalStranding Scheme, several thousand modern and historical records were submitted between 1910 and 2018 to MarineEnvironmental Monitoring and its turtle database (Botterell et al . 2020). Not bad for some cold rocks in the North Atlantic, especially considering Ireland doesn’t even have any snakes!

Besides being an awesome yet unusual sight to be hold, records of sea turtle strandings, sightings and incidental capture within Irish and UK waters can be vitally important for conservation. This is because they provide valuable insights into relatively complex and poorly understood life histories, abundance, and dispersal, whilst also shedding light on the impacts of many anthropogenic interactions, such as oil spillages and pollution, by-catch, climate change, vessel collisions, and coastal development.

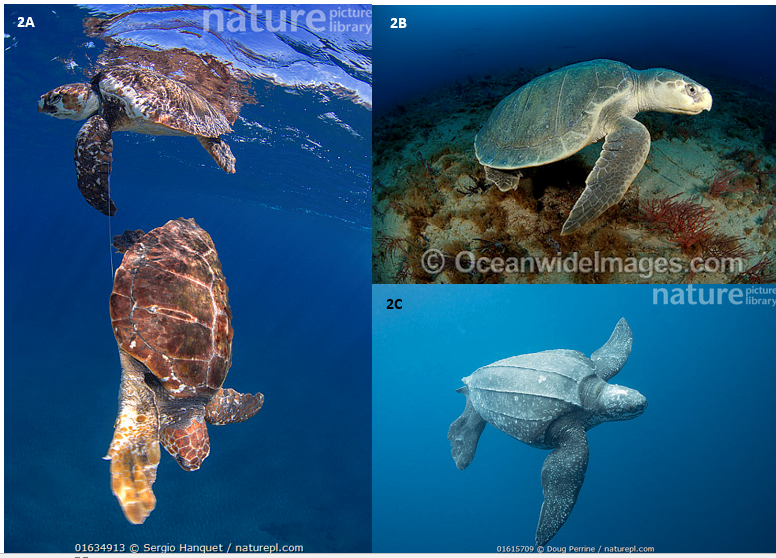

Botterell et al . (2020) recently summarised trends in sea turtle sightings within the UK and Ireland over the last century, relating these records to known life histories and global events. Overall, six species of sea turtle have been documented within our waters, including 11 green sea turtles ( Chelonia mydas – Figure 1A), a single olive ridley ( Lepidochelysolivacea – Figure 1B) off the coast of Anglesey in 2016, and a single hawksbill( Eretmochelys imbricata - Figure 1C) near Cork in 1983. However, most records belong to loggerheads (Caretta caretta - 240 records, Figure 2A), Kemp’s Ridleys ( Lepidochelys kempii - 61 records, Figure 2B), and leatherbacks (Dermochelys coriacea - 1683 records, Figure2C). Of the1997 records, 1362 were attributed to confirmed sightings (93.3% still alive),492 were documented as strandings (23.8% still alive), and the remaining 143records were assigned as captures within fishing nets, lines and ropes (69.2% still alive, Figure 2A). Those by-caught were predominantly leatherbacks ( D. coriacea = 135, C. caretta = 6, L. kempii = 2).

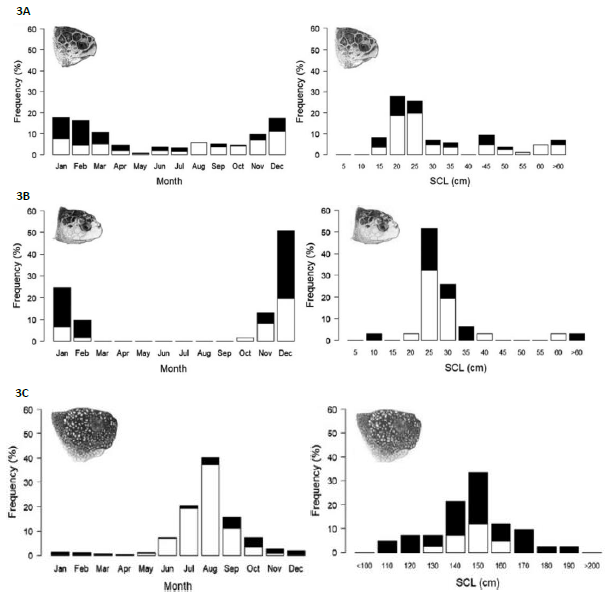

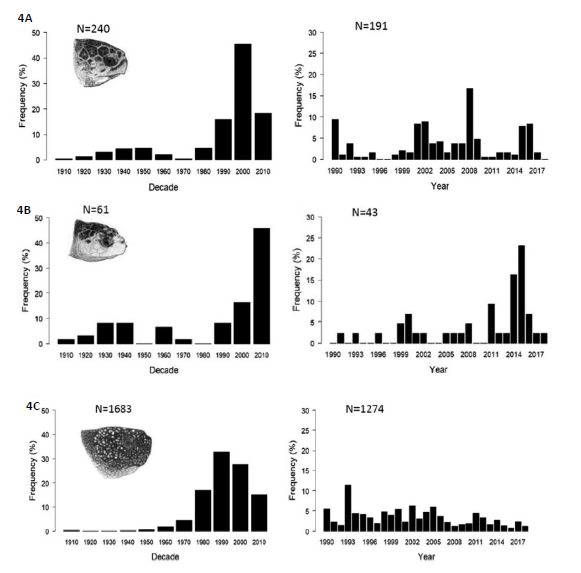

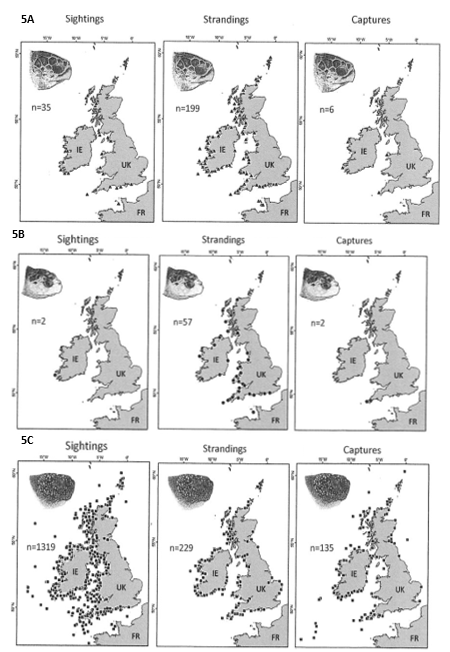

Generally speaking, hard-shelled sea turtles (i.e. C.caretta and L. kempii ) were recorded most frequently as juveniles within the boreal winter months (December to February) when the North-eastAtlantic waters are at their coldest (figure 3A and 3B). Comparatively, the singular soft-shelled species, D. coriacea , was most frequently recorded as adults during the boreal summer (June to October – figure 3C). Whilst recordings of all three species generally increased between 1910 and 2000, they have since decreased annually within leatherbacks (figure 4A - C). Furthermore, although documented recordings of all three species were predominantly concentrated around the west coast of the UK and Ireland, D. coriacea was the most widely dispersed and unlike their hard-shell counterparts, leatherback records did not significantly decrease at higher latitudes (figure 5A - C).

A variety of factors can help explain these trends. First and foremost, shifts in knowledge, awareness, and the promotion of sea turtles, science and associated reporting schemes will directly influence the amount of records received. More people looking out for and able to identify sea turtles obviously results in more data being collected. Secondly, there are clear biological and ecological explanations as to why leatherbacks are more prevalent within the North EastAtlantic than their hard-shelled brethren. Whilst most sea turtles are ectothermic (rely on environmental sources of heat to regulate their internal body temperature), D. coriacea are largely categorised as endothermic and are thus able to generate or otherwise retain body heat thanks to their anatomy. This means that leatherbacks are more thermo-tolerant than other species of sea turtle, enabling them to readily inhabit cooler waters and occupy higher latitudes. Similarly , C. caretta and L. kempii are seemingly more thermo-tolerant than other hard-shelled species such as E. imbricata , explaining why they are more readily sighted within our waters.

Thermoregulation in tandem with abiotic factors such as wind patterns, surface currents, water temperatures and coastal morphology can explain spatial patterns within the recorded data to some extent. The long and short of this being that as these factors vary both seasonally and now more so annually, in part due to climate change, they influence where sea turtles can go and when, particularly during key life stages. For example, the North Atlantic currents present whilst juveniles disperse are likely responsible for why so many of the recorded hard-shelled sea turtles are sub adults. Less thermo-tolerant species often migrate and disperse in conjunction with water temperature, which is often dictated by the abiotic environment (i.e. thermal currents, wind temperatures) and can help explain range shifts or seasonal patterns. Furthermore, if the water temperature drops suddenly before the sea turtles have managed to get to warmer waters they can be ‘cold-stunned’ due to their internal temperature dropping below their metabolic threshold. Such individuals can then be carried by strong currents and become stranded.

Similarly, thermoregulation and abiotic variation also influence leatherback distribution, but also in terms of prey abundance.This is because during the boreal summer, Irish and UK waters become an all you can eat buffet of jellyfish, the leatherback’s preferred prey item, due to their populations peaking and concentrating around our coasts due to temperatures and seasonal currents etc. More food, more turtles.

Most other influencing factors directly relate to the reproduction, recruitment and dispersal of sea turtles. This can be as simple as the Bay of Biscay seemingly being a residency spot for loggerheads nearby within the North East Atlantic, increasing the likelihood of such individuals being found along our coastlines. Another factor explaining increased prevalence is that most sea turtle species became protected during the 1960’s, in turn leading to increased conservation efforts and thus larger numbers of offspring being produced during subsequent years (i.e. due to eggs no longer being intensively harvested). Similarly, factors such as the implementation of turtle excluder devices within fishing nets should reduce the number of individuals being by-caught, meaning that more will reach sexual maturity and reproduce. However, factors such as increased fishing effort, coastal developments destroying or disturbing nesting sites, climate change influencing nest temperatures, sex determination and successful incubation, and environmental disasters such as the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill in 2010 could all contribute towards the observed declines in recent years, influencing how many hatchlings are recruited, of which genders, and how many adults reach sexual maturity let alone reproduce.

Whilst the exact causes of annual patterns in sea turtle strandings and sightings remain somewhat unclear, contributing factors can be readily identified within the data collected and such information can be utilised to help guide conservation efforts, legislation and coastal developments etc. to the benefit of the species concerned as well as ourselves. This highlights the importance of citizen science and these programmes. To find out more, get involved, and report sightings or records to the OBSERVERS APP or directly though out website in "Home", "Log Wildlife".

References:

Botterell, Z.L.R., Penrose, R.,Witt, M.J., and Godley, B.J. (2020). Long-term insights into marine turtlesightings, strandings and captures around the UK and Ireland (1910 – 2018). Journalof the Marine Biology Association of the United Kingdom. 1-9.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE