Baleen whales lose teeth in the womb in the last stage of development!

Baleen whales in utero, begin the formation of several dozens of teeth in upper and lower jaws. During the late developmental stage as the tooth germs disappear, keratinous baleen plates start to form in the upper jaw, to provide the new calf with an efficient food-collecting mechanism for filter-feeding small fish and krill. These new findings of prenatal teeth in modern fetuses may indicate evolutionary "leftover", as baleen whale ancestors had two generations of teeth and never developed baleen.

Recent studies have indicated that through analysis of modern baleen whale's prenatal tooth germs, the ancestors of certain whale species such as the bowhead whale ( Balaena mysticetus

), may be divulged (Thewissen et al.,

2017). A new study published in The Anatomical Record

Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology,

on prenatal development of tooth germs in humpback whales ( Megaptera novaeangliae)

also indicated that the macroevolutionary process of tooth loss occurs throughout gestation (Lamzetti et al.,

2018).

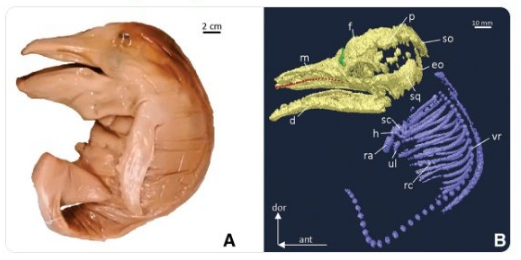

The cranial morphology of five juvenile humpback whale fetus were analysed using iodine enhanced and traditional CT Scanning to visual the internal anatomy. The results showed that tooth germs within the developmental sequence, confirms that the tooth‐to‐baleen transition occurs in the last one‐third of gestation. Researchers also analysed cranial shape development which showed a progressive elongation of the rostrum and a resulting posterior movement of the nasals relative to the braincase.

Similar studies also found that with the degeneration of the tooth germ, the baleen whale germ begins development for minke whales ( Balaenoptera acutorostrata)

(Ishikawa et al

., 1999).

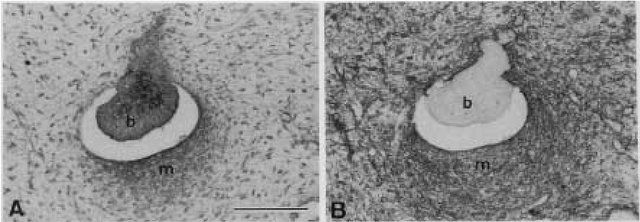

Mysticetes have thus, been shown to develop tooth germs during ontogeny. These teeth germs are aggregations of cells that eventually form teeth, reach the bell stage and are either mineralized, or resorbed, leaving no trace remains post partum. Similarly to in utero, in the fossil the transition from ancestral raptorial feeding to filter feeding through tooth loss is well documented in the fossil record.

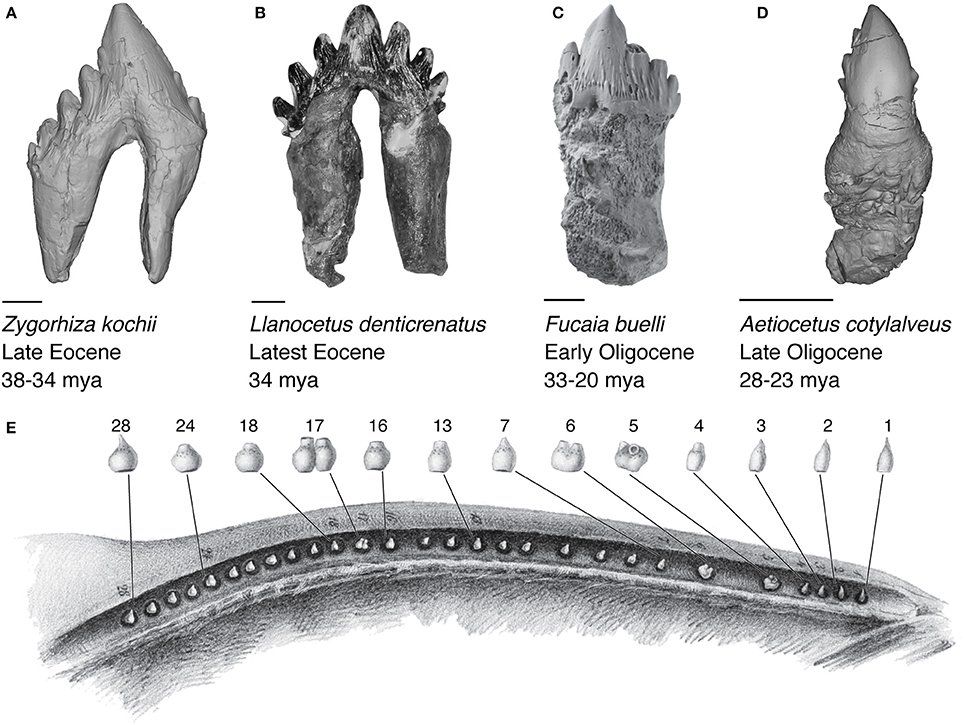

The precise timing of baleen origin is still uncertain, although it likely occurred sometime between the latest Eocene (~34 million years ago) to the latest Oligocene (~23 mya). During this period of geologic time, ocean circulation patterns, and climate varied dramatically at the Eocene-Oligocene boundary ( Prothero and Ivany, 2003 ), implicating an important link between environment and morphological innovation in cetacean evolution. The mechanism to which this evolutionary process of tooth loss to baleen whale formation is unknown although previous studies suggestthat a transitional step in stem mysticetes included taxa bearing neither teeth nor baleen, described four independent, non-inclusive hypothesis for the formation of baleen in whales( Peredo et al., 2017 );

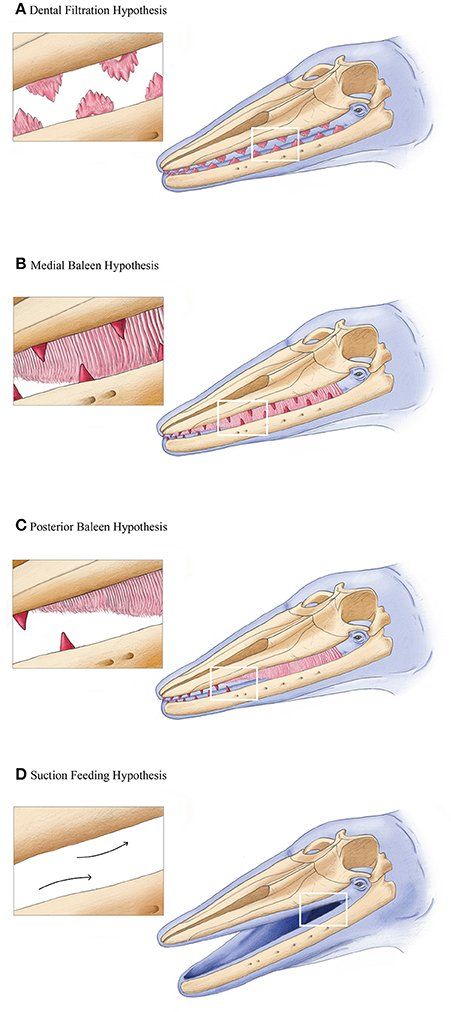

1). The first hypothesis about feeding in stem mysticetes species such as Llanocetus denticrenatus from the late Eocene of Seymour Island, Antarctica ( Mitchell, 1989 ). proposes a filter feeding mode using the denticulate cusps of their teeth as a sieve, in a similar manner to crabeater seals ( L. carcinophagus ; Fordyce, 1989 ; Ichishima, 2005 ). Initial studies on the range of available evidence, suggested the origin and evolution of baleen in mysticetes defied simple explanations as the teeth of previously described toothed mysticetes are too few, too small, too simplified, or too worn to be effective in filtering ( Fitzgerald et al ., 2010 ). The dental filtration hypothesis argued that filter feeding evolved first using denticulate cheek teeth, and that baleen later evolved as a secondary structure to increase feeding efficiency.

2). The medial baleen hypothesis proposed that embryonic baleen evolved intermediate to a functional dental row ( Deméré and Berta, 2008 ; Deméré et al ., 2008 ; Ekdale et al ., 2015 ).

3). The posterior baleen hypothesis suggested that functional baleen evolved behind residual adult teeth kept at the distal tip of the rostrum and dentaries, with the dentition and baleen aligned in the rostrum ( Boessenecker and Fordyce, 2015 ).

4). The suction feeding hypothesis indicated that suction feeding was the ancestral feeding method, and suggested a transition first from reportorial feeding to suction feeding and then subsequently to bulk filter feeding ( Marx e

t al

., 2015).

Read more here: https://www.orcireland.ie/discovery-of-the-missing-link-in-whale-evolution1.

References

;

Boessenecker, R. W., and Fordyce, R. E. (2015b). A new genus and species of eomysticetid (Cetacea: Mysticeti) and a reinterpretation of “ Mauicetus” lophocephalus

Marples, 1956: transitional baleen whales from the upper oligocene of New Zealand. Zool. J. Linn. Soc.

175, 607–660. doi: 10.1111/zoj.12297.

Ekdale, E. G., Deméré, T. A., and Berta, A. (2015). Vascularization of the Gray Whale palate (Cetacea, Mysticeti, Eschrichtius robustus

): soft tissue evidence for an alveolar source of blood to baleen. Anat. Rec.

298, 691–702. doi: 10.1002/ar.23119.

Deméré, T. A., and Berta, A. (2008). Skull anatomy of the Oligocene toothed mysticete Aetioceus weltoni

(Mammalia; Cetacea): implications for mysticete evolution and functional anatomy. Zool. J. Linn. Soc.

154, 308–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2008.00414.x

Deméré, T. A., McGowen, M. R., Berta, A., and Gatesy, J. (2008). Morphological and molecular evidence for a stepwise evolutionary transition from teeth to baleen in mysticete whales. Syst. Biol.

57, 15–37. doi: 10.1080/10635150701884632.

Fitzgerald, E. M. G. (2010). The morphology and systematics of Mammalodon colliveri

(Cetacea: Mysticeti), a toothed mysticete from the oligocene of Australia. Zool. J. Linn. Soc.

158, 367–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00572.x

Fordyce, R. E. (1989). Origins and evolution of Antarctic marine mammals. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ.

47, 269–281. doi: 10.1144/GSL.SP.1989.047.01.20

Ichishima, H. (2005). Notes on the phyletic relationships of the Aetiocetidae

and the feeding ecology of toothed mysticetes. Bull. Ashoro Mus. Paleontol.

3, 111–117.

Ishikawa, Hajime & Amasaki, Hajime & , H.Dohguchi & Furuya, A & Suzuki, Katsushi. (1999). Immunohistological distributions of fibronectin, tenascin, typeⅠ, Ⅲand Ⅳ collagens, and laminin during tooth development and degeneration in fetuses of minke wale, Balaenoptera acutorostrata

. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science

. 61. 227-232.

Lanzetti, A., Berta, A., Ekdale, E.G., (2018). Prenatal Development of the Humpback Whale: Growth Rate, Tooth Loss and Skull Shape Changes in an Evolutionary Framework. The Anatomical Record Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.23990.

Marx, F. G., Tsai, C.-H., and Fordyce, R. E. (2015). A new Early Oligocene toothed “baleen” whale (Mysticeti: Aetiocetidae) from western North America: one of the oldest and the smallest. Royal Society of Open Science.

2, 1–35. doi: 10.1098/rsos.150476 .

Mitchell, E. D. (1989). A new cetacean from the late eocene la meseta formation, Seymour island, Antarctic Peninsula. Canadian Journal of Fish. Aquatic Sciences.

46, 2219–2235. doi: 10.1139/f89-273

Peredo, C. M., and Uhen, M. D. (2016). A new basal chaeomysticete

(Mammalia: Cetacea) from the Late Oligocene Pysht Formation of Washington, USA. Pap. Palaeontol.

2, 533–554. doi: 10.1002/spp2.1051

Prothero, D. R., and Ivany, L. C. (2003). From Greenhouse to Icehouse: The Marine Eocene-Oligocene Transition

. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Thewissen, J. G., Hieronymus, T. L., George, J. C., Suydam, R., Stimmelmayr, R., and McBurney, D. (2017). Evolutionary aspects of the development of teeth and baleen in the bowhead whale. Journal of Anatomy.

doi: 10.1111/joa.12579.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE